Chapter 2: Cultures and customs in the hospital, immersion experience of a BME student

By Andrea Gardner

Being immersed in a hospital setting for the first time can be an intimidating experience for anyone. Hospitals have rigid organizational structure and strict policies that are not always immediately apparent to an unexperienced bystander. Many biomedical engineers have never had any significant clinical experience and, though some may feel perfectly comfortable and confident with the idea of being immersed in a hospital setting, others may not. Collaboration between biomedical engineers and clinicians is critical to the advancement of medical technology. For this reason, the clinical exposure of engineers is of utmost importance. This chapter hopes to educate biomedical engineers about the cultures and customs of a hospital so that they may feel more comfortable in a clinical setting and so that collaboration between engineers and clinicians, and the idea generation which hopefully results, may be fostered.

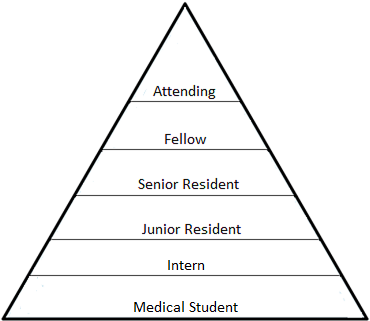

2.1 Medical hierarchiesUpon entering a hospital, one of the most difficult aspects of medical practice to grasp is the medical hierarchy and determining who is in charge. Everyone is dressed in white coats or scrubs and they are all referred to as doctors. However, engrained in the medical education system is a hierarchy, in which doctors start as medical students and may work their way up the pyramid. The main roles seen in a teaching hospital in the US are depicted in Fig.2.1.

A medical student, or med student, is a person who is still enrolled in a graduate medical program and has not yet earned their MD.

An intern is a graduate of medical school, but does not yet have a license to practice unsupervised clinical medicine. Often, an internship is part of a multi-year residency, in which residents in their first year are referred to as interns. Upon completion of the one-year internship or first year of residency, the doctor may practice as a general practitioner without supervision

A medical resident is someone who holds a medical degree and wishes to pursue training in a specialty field. Residencies can last 3 to 7 years depending on the specialty, for example, a residency in emergency medicine averages around 3 years, while a residency in urology averages around 5 years. Most hospitals require that the attending physician supervise all medical decisions made by residents.

A junior resident is someone who is in the first half of his or her residency.

A senior resident is someone who is in the second half of his or her residency. Senior residents are often given more responsibility and independence within the hospital than junior residents.

A fellow is someone who has completed their residency program and obtained medical license and seeks training in a sub-specialty through a fellowship. Examples of what someone may pursue as a fellowship include: cardiology, endocrinology, immunology, neonatology, oncology, and more. Completion of a fellowship would allow that doctor to practice that sub-specialty without supervision.

The attending physician must have completed a residency program and often has fellowship training as well. The attending physician is responsible for all aspects of patient care in his or her ward, often through supervisory and teaching interactions with residents, interns, and medical students.

The hierarchy of graduate medical education is well established, and students of the medical education system are accustomed to respecting those further along, but how should engineers approach this unfamiliar educational pyramid?

First, one must never forget that doctors, just like patients, nurses, yourself, and everyone else in the world, are just people. And as with everyone in the world, people have different personality types, different experiences, and different perspectives that are constantly influencing actions and reactions to situations. Still, though, some general behavioral advice on how to act when working with doctors may be helpful.

Step 1: Introduce yourself

"Hi, I'm Andrea, I'm a visiting biomedical engineering student from Cornell Ithaca."

When meeting someone with a hospital badge, first introduce yourself and explain your role, then allow them to introduce themselves. If it is not apparent by their badge or their introduction, you can ask what their role is. Every person in every role in the hospital, not just doctors, can help add perspective and understanding to your experience. Make sure to take complete advantage of the vast knowledge hiding in the minds of those around you.

Step 2: Give them a reason to interact with you

"As part of my graduate research, I design and build low-cost medical equipment, but I've never really seen medicine in action. I'd love to watch how you use tools to interact with patients to gain that perspective. Additionally, if you have any complaints about current tools or lack of tools, we might be able to work together to design something new."

Most doctors gladly disseminate their knowledge to others in their profession and many doctors strive to educate more than just their peers, but what can you do if you are placed with a doctor who does not see the use in sharing knowledge with you, the observer?

In this case, it is sometimes helpful to try to learn from the residents. Residents are known for being more open, but even residents can sometimes overlook the importance of you being in the room.

An engineer is at the hospital to observe and learn about the clinical practice of medicine and areas of potential improvement. This is made more difficult if the medical experts at the hospital are unwilling to share their knowledge. It can be helpful to mention that, as an engineer, you plan to strive to improve various aspects of health care through technological advancement and innovation. The intent of this is to establish your value as both an intelligent and competent professional and an individual whose goal is to improve something that could be important to the doctor.

If, despite your best efforts, you cannot find a physician, resident, or other healthcare professional to share their knowledge and experiences, make the best of your situation. Attempting to force others to want to interact with you will lead to a negative experience for both you and those with whom you are working. Instead, acknowledge the situation, attempt to absorb as much of the experience as you can, and in the future look for other healthcare workers who may be more willing to indulge your intellectual curiosities.

Step 3: Joining rounds and determining what makes a good question

Doctors perform rounds together to keep each other updated on each patient. Rounds can vary significantly from department to department. Often radiology rounds consist of a gathering of doctors around a table discussing each patient's symptoms while viewing that patient's x-ray, CT, or MRI at the front of the room. On the contrary, emergency department rounds happen during shift handoffs and the doctors physically meet with each patient as a group and try to formulate a plan. What both of these scenarios have in common is that during rounds, a single patient is focused upon and discussed amongst multiple doctors before moving onto the next patient. Medicine is often a top-down process, with the attending always supervising and directing patient care, but rounds give an opportunity for more democratic discussions to occur between doctors of all training levels.

Joining rounds can be intimidating (Fig.2.2). If you are not prepared, it can feel like you are being thrown case study after case study and barely given enough time to hunt for the recognizable Latin or Greek roots in the first symptom listed before the discussion of the next case begins.

Before going on rounds, doctors print out patient cheat sheets that show abbreviated notes of each patient's time in the hospital, which include the patient's primary condition, current medications, and intake date. You are allowed to request a copy of this information so long as you protect it in accordance with the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Getting to rounds early will allow you to review the patient information and discover any questions that can be more easily answered ahead of time. For example, instead of getting lost in words during rounds, one of the residents or a discreet Internet search can quickly tell you that xerostomiath is simply dry mouth.

This applies outside of rounds as well, but especially during rounds: always carry a pocket sized notebook and a pen. Even if you prepare as much as possible, doctors may still be throwing around terminology and prescribing procedures and treatments of which you have never heard. Write it all down, as this will allow you to ask or look up questions later.

If the day is slow, the physicians may welcome questions from you during rounds. However, typically rounds are chaotic and it can be very hard to get a word in on the side. If you do find an opportunity to ask a question, you want to make sure it is a good one.

Only you can determine which question to ask in order to get the most out of your experience, but here are some aspects of consideration to help determine if a question is worth asking during rounds:

1. Can I look this up on the Internet later?

If the answer is yes, it is probably not worth asking during hectic rounds.

2. Is it possible that asking this question in front of the patient could make the patient uncomfortable or distressed?

If your answer is even maybe, you should save your question for later when you are not within hearing range of the patient.

3. Will knowing the answer to this right now change my experience?

While I was rounding in the pediatric ICU, I kept hearing a word I did not know over and over again. I tried to write it down, but was not able to spell what I was hearing. Though I was embarrassed to ask because of how often they were using the word, asking what it meant for someone to be tachypneic and receiving an answer (tachypnea: rapid breathing) exponentially increased my understanding of each patients' condition from that point forward and allowed me to focus on the people in front of me rather than a word.

4. Could asking this question potentially shift the doctors' perspective in a way that would benefit the patient?

Just because you do not have years of medical training does not mean you should not listen to your intuition. Maybe you read a paper once about a rare disease that the patient in front of you seems to fit. When framing the question of whether or not the doctors have already looked into a certain disease or treatment, always make the humble assumption that they have already thought of it. Even if they have already thought of it, discussion on why they do not believe a patient has a particular disease may encourage follow-up testing or at least interesting discussion within the group.

Conversing with patients, obviously in a way that does not impede their care, can be enriching for both you and the patient. As most engineers have never been given the opportunity to converse with patients on a daily basis, here are some general guidelines on how to interact with those who are being treated in a hospital.

Step 1: Introduce yourself

"Hi Mr. Johnson, my name is Andrea, I'm a biomedical engineering graduate student."

Be honest and open about your position as a graduate student observer. Sometimes they will even be curious and want to learn more about your program.

If the patient will be conscious for the procedure, you should get their permission for you to ask questions to the doctor performing the procedure as it is done. Questions, or even the answers to your questions, may make the patient feel anxious or uncomfortable. If the patient prefers that you not ask questions during the procedure, jot down your questions in a notebook and ask the attending physician or residents later.

Step 2: Get to know the patient and connect with them

"So, Mr. Johnson, tell me a little more about yourself, where are you from?"

Talking to patients can be difficult without knowing their background and what might trigger upset, so try to stick to neutral subjects. You can ask how they are doing, but because they are in a hospital their response may be negative. Not every patient will have friends and family waiting for them, so wait until they bring up people in their life before asking about family. A more neutral question you can start with is "Where are you from?" Everyone has a story to tell and if the patient is in the mood for talking, this is a good place to start. If the patient prefers not to talk, do not try to force it. Just let them know that you are around if they need anything.

Step 3: Do something about it!

"Hey Tom, Mr. Johnson is really uncomfortable, do you think you can help him shift when you get a chance? Thanks so much!"

In non-life threatening cases, you, as an observer, should be adhering to a hands-off policy. You can still help the patient, though, if he or she needs anything by signaling for the person who can help. For example, if the patient needs to shift in the bed or manipulate the IV, listen and then find a nurse to care for the patient.

Additionally, July and August can be an especially difficult time to be a patient. This is the time in which new residents and fellows show up and are learning the ropes from the senior physicians. A new resident may be performing the procedure and the attending may be yelling orders from across the room. I have seen a patient's heart rate increase by 30bpm, as she laid there with the junior resident yelling back to the attending while repositioning the chest tube over and over again. In times like these, go back to step 2. Talk to the patient and take their mind off of what is happening.

Step 4: Keep them informed

"Good to see you again, Mr. Johnson, just wanted to let you know that your CT scan uploaded to the computers and we're just waiting for a read from the radiologist now. Hopefully we'll have some updates for you soon!"

If your patient or the patient's family is waiting on results, do your best to keep them informed! Again, you can remind them that you have little authority to take action as a student, but most of the time the patient and/or family will just be happy to hear that someone is thinking about them and that they are not getting lost in the medical ether. This step is especially important in busy areas of the hospital, such as the emergency department, where patients often feel forgotten, as the doctors are inundated attempting to see everyone. You can make a huge difference just by talking to them and letting them know that everything is moving forward, even if slowly.

Entering a clinical setting for the first time as an engineer can be an intimidating and daunting experience. Garnering valuable information and learning from the clinical experience can be an even more difficult endeavor. I hope that gaining a general understanding of hospital culture and protocol has made you feel more prepared to enter the hospital as an observing student.